By Dr. Stephen Soldz

Psychoanalysis and empirical research have not always been on friendly terms. Recent decades, however, have seen an increase in psychoanalytically-informed research. One area where this research has expanded is in assessing the outcomes of psychodynamic or psychoanalytic therapies. (In brief, psychodynamic therapies are based upon psychoanalytic principles but may not include all the features, such as use of a couch, of traditional psychoanalysis.)

Much of the research on the outcomes of psychodynamic psychotherapy has focused upon short-term, if not explicitly time-limited treatments. In general, this research demonstrates that short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy is better than no treatment and is roughly equivalent in outcomes to other types of treatment.

Study of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (LTPP) has proven more difficult. Random assignment, the preferred technique for making strong conclusions regarding therapy efficacy, is difficult when patients are assigned to long treatments, due to patient resistance to randomization and their tendency to drop out of longer treatments that are either not working or working well enough that patients feel they’ve had enough.

Random assignment to different treatment conditions, or a randomized controlled trial (often called an RCT) is preferred because, given reasonably large sample sizes, the randomization radically reduces the likelihood that differences in outcomes between treatments are due to extrinsic factors such as differences between patients in the groups being compared. Thus, when a randomized controlled trial is well-designed and successfully conducted, one can be reasonably assured that outcome differences reflect differences in the efficacy of the treatments under comparison.

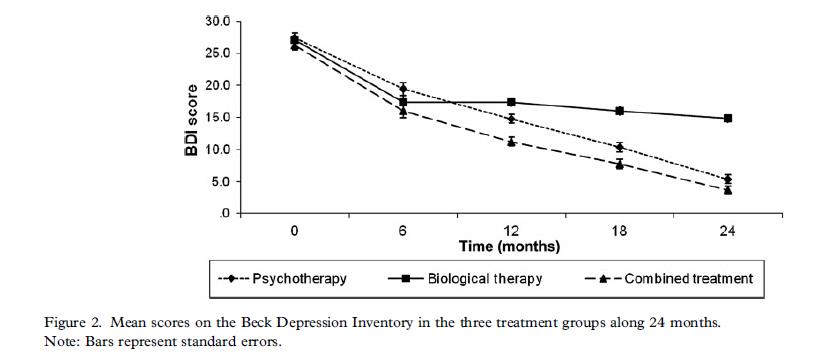

In the past few months, two studies have appeared that successfully compared the outcomes of patients randomly assigned to either LTPP (long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy) or other active treatments. One of these studies by Andre Bastos and colleagues, conducted in Brazil, compared two-year-long LTPP with fluoxetine (trade name Prozac) treatment and with combined LTPP- fluoxetine treatment with a moderately depressed relatively young adult population. Their outcome measure was the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), perhaps the most commonly used depression severity questionnaire.

Bastos et al. found that at six months, patients receiving the combined treatment had significantly lower BDI scores than those receiving LTPP. However, these differences were no longer significantly different at 24 months. At that point both LTPP alone and combined LTPP fluoxetine were significantly more effective (lower BDI score) than fluoxetine alone, while the two groups receiving LTPP did not exhibit significant differences. These effects can best be seen in the following figure from the paper:

The figure shows a striking pattern. While all three treatment conditions had strong effects in the first six-months of treatment, the effects of the drug alone leveled off at that point, still in the clinically distressed range of the BDI. In contrast, those receiving LTPP exhibited continued (essentially linear) improvement for the remaining 18 months they were in treatment. As proponents of long-term therapy would claim, longer-term PDT in this study led to greater improvement as treatment progressed, something not seen with fluoxetine.

The results of near equivalent results of the LTPP (long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy) with fluoxetine early in treatment, at 6-months, are consistent with prior studies finding short-term PDT often as effective as drug therapy for major depression in a primary care setting. Thus, a 2008 study out of Finland found 16 weeks of PDT had similar outcomes to fluoxetine in terms of decreased depressive symptoms and increased social functioning. The Bastos et al. study thus raises the possibility that studies comparing drugs and psychotherapy may have used too short a time frame to show a superior effect for therapy. However, this superiority is only a possibility until it can be demonstrated in several independent well-designed studies.

Part II next week will discuss another recent randomized controlled trial of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (LTPP) versus treatment as usual, this one for sufferers from very hard to treat treatment-resistant depression.