By Dr. Stephen Soldz

In Part I last week, I discussed the Bastos et al. study out of Brazil that found long-term psychodynamic therapy (LTPDT) to have better outcomes than fluoxetine after 24 months of treatment. This week I’ll take a look at another recent study involving another randomized controlled trial (RCT) of LTPDT (called by the authors Long-term Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy or LTPP). In a study out of Britain, Peter Fonagy and colleagues examined the value of LTPDT as a therapy for treatment-resistant depression.

Patients in this study were in an episode of major depression that had already lasted at least two years and had a minimum of two failed treatment attempts. (In fact, the mean number of prior treatments was nearly four.) One hundred twenty-nine patients met inclusion criteria and were randomly assigned either to receive 60 sessions of PDT therapy over 18 months or treatment as usual (TAU), following British government guidelines. Both groups received about the same number of medications. In addition to the medications, TAU included brief psychosocial treatments such as CBT (cognitive behavior therapy) or counseling. Patients were followed and administered a battery of assessment instruments several times over three and one half years (42 months); follow-up thus extended two years after the end of the PDT treatment.

Complete remission of depression – symptoms below a certain threshold – was rare in both groups. Nearly 15% of those receiving LTPDT exhibited full remission at 42 months, compared to 4.4% of those in the TAU group. Partial remission was more common. At the 18-month end of treatment, 32.1% of those receiving LTPDT had partial remission, compared to 23.9% in the TAU group. During follow-up, the difference increased at each measurement point until at the 42-month follow-up, 30.0% of the LTPDT group experienced partial remission vs. 3.9% for the TAU group, a nearly eight-fold difference.

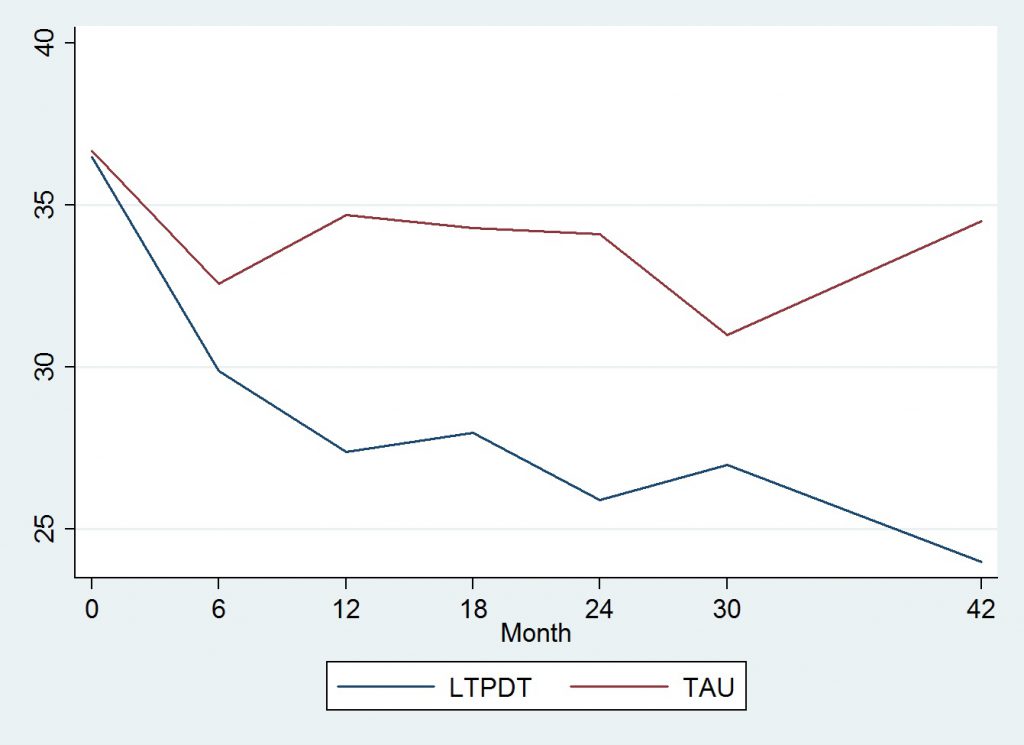

A similar pattern was found for the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores, which were significantly different at 18 months and at 42 months follow-up. For the TAU group, the following figure I’ve constructed from data in Fonagy et al.’s Table 3 shows no real reduction in BDI scores for the TAU group, while those for the LTPDT group decreased during and after treatment completion.

Both the Bastos et al. and Fonagy et al. studies contribute to the database supporting long-term psychoanalytically oriented treatment for depression. In both cases, the effects of the treatment versus the control conditions took some time to become apparent. In the Bastos study, medication slightly improved outcomes at six months, but only the therapy led to continued improvement. In the much more severely disturbed treatment-resistant population studied by the Fonagy group, with some measures the therapy effects became apparent only during the two years of follow-up after the 18 months of treatment were completed.

These findings are consistent with the idea that psychoanalytically informed treatments help patients develop more adaptive patterns of coping that help them over time and that the benefits of these changes may continue or even increase after therapy is completed. The Fonagy et al. study suggests that these new coping patterns are retained post-therapy, as psychoanalytic theory suggests should occur.

Examining the results of these studies, one might wonder what would have occurred if the therapy had continued longer. Would there have been continued improvement, or would the benefits have declined over time? These studies add significantly to the evidence base supporting long-term psychodynamic therapy as an effective treatment for depression. They also suggest that many of the benefits of longer-term treatments take time to develop and that studies should examine patients over fairly long periods of time, including after treatment is completed.

However, the relatively low remission rates among patients in the Fonagy et al. study suggests that while 18 months of LTPDT is considerably better than usual treatment, it is far from a panacea. Longer, or otherwise improved treatments are needed to return these chronically impaired individuals to a more normal range of functioning.

Researchers know well that one, or even two studies are not definitive. It is to be hoped, however, that these studies will increase interest in studying psychodynamic therapies. It is also notable that neither of these studies was conducted in the United States. Hopefully the National Institute of Mental Health will pay attention to these studies and support research here of longer-term therapies, including psychoanalytically informed ones.